Block Floating-Point Background¶

Block Floating-Point Vectors¶

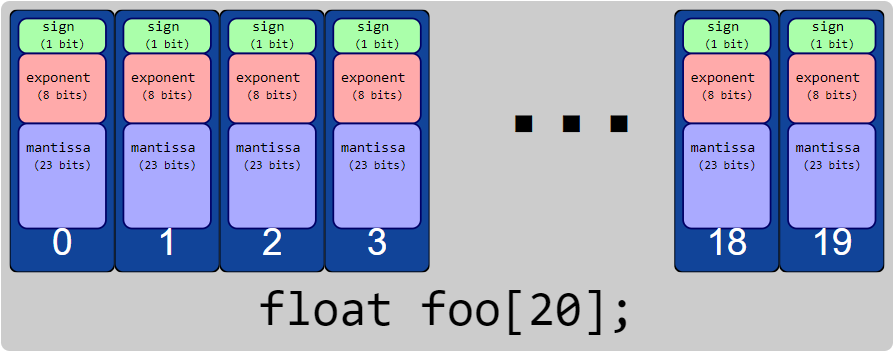

A standard (IEEE) floating-point object can exist either as a scalar, e.g.

//Single IEEE floating-point variable

float foo;

or as a vector, e.g.

//Array of IEEE floating-point variables

float foo[20];

Standard floating-point values carry both a mantissa \(m\) and an exponent \(p\), such that the logical value represented by such a variable is \(m\cdot2^p\). When you have a vector of standard floating-point values, each element of the vector carries its own mantissa and its own exponent: \(m[k]\cdot2^{p[k]}\).

By contrast, block floating-point objects have a vector of mantissas \(\bar{m}\) which all share the same exponent \(p\), such that the logical value of the element at index \(k\) is \(m[k]\cdot2^p\).

struct {

// Array of mantissas

int32_t mant[20];

// Shared exponent

int32_t exp;

} bfp_vect;

Headroom¶

With a given exponent, \(p\), the largest value that can be represented by a 32-bit BFP vector is given by a maximal mantissa (\(2^{31}-1\)), for a logical value of \((2^{31}-1)\cdot2^p\). The smallest non-zero value that an element can represent is \(1\cdot2^p\).

Because all elements must share a single exponent, in order to avoid overflow or saturation of the largest magnitude values, the exponent of a BFP vector is constrained by the element with the largest (logical) value. The drawback to this is that when the elements of a BFP vector represent a large dynamic range – that is, where the largest magnitude element is many, many times larger than the smallest (non-zero) magnitude element – the smaller magnitude elements effectively have fewer bits of precision.

Consider a 2-element BFP vector intended to carry the values \(2^{20}\) and \(255 \cdot 2^{-10}\). One way this vector can be represented is to use an exponent of \(0\).

struct {

int32_t mant[2];

int32_t exp;

} vect = { { (1<<20), (0xFF >> 10) }, 0 };

In the diagram above, the fractional bits (shown in red text) are discarded, as the mantissa is only 32 bits. Then, with \(0\) as the exponent, mant[1] underflows to \(0\). Meanwhile, the 12 most significant bits of mant[0] are all zeros.

Headroom is the number of bits that a mantissa can be left-shifted without losing any information. In the the diagram, the bits corresponding to headroom are shown in green text. Here mant[0] has 10 bits of headroom and mant[1] has a full 32 bits of headroom. (mant[0] does not have 11 bits of headroom because in two’s complement the MSb serves as a sign bit). The headroom for a BFP vector is the minimum of headroom amongst each of its elements; in this case, 10 bits.

If we remove headroom from one mantissa of a BFP vector, all other mantissas must shift by the same number of bits, and the vector’s exponent must be adjusted accordingly. A left-shift of one bit corresponds to reducing the exponent by 1.

In this case, if we remove 10 bits of headroom and subtract 10 from the exponent we get the following:

Now, no information is lost in either element. One of the main goals of BFP arithmetic is to keep the headroom in BFP vectors to the minimum necessary (equivalently, keeping the exponent as small as possible). That allows for maximum effective precision of the elements in the vector.

Note that the headroom of a vector also tells you something about the size of the largest magnitude mantissa in the vector. That information (in conjunction with exponents) can be used to determine the largest possible output of an operation without having to look at the mantissas.

For this reason, the BFP vectors in lib_xs3_math carry a field which tracks their current headroom. The BFP functions in the high-level API use this property to make determinations about how best to preserve precision.